Kasole of the Munyaga group beats his chest for us! Watch a video here. Who is Kasole? Find out here.

Having returned from guiding my nineteenth gorilla trek in fourteen months, I thought I’d share some of the insight that I have gained so that if you are considering a trip to see mountain gorillas you have more than the standard info pack you might receive from standard operators.

I personally prefer trekking in Virunga National Park in the Democratic Republic of Congo. The experience is slightly less regimented, sometimes disorganized, but is undoubtedly more intimate. The history of the gorilla groups in this article therefore applies to the groups in DRC, however, the Mountain gorillas are essentially the same wherever you are in the Virunga Massif.

Below are some frequently asked questions (see my next post for some history into the make up of the six of the gorilla groups you’ll most likely visit in DRC):

How many species of gorillas are there?

There are 2 species of gorilla- the eastern gorilla (Gorilla beringei) and the western gorilla (Gorilla gorilla). The former is found in Virunga and split into two subspecies- the Mountain Gorilla of which half live in Virunga National Park, and the Eastern Lowland Gorilla (Gorilla beringei graueri) found in northern parts of the park and in Kahuzi-Biega National Park south of Lake Kivu.

How many mountain gorillas are left in the wild?

This question is a bit of a misnomer because mountain gorillas don’t survive outside of the wild. In fact, the only place where they survive in captivity is at the orphanage at Mikeno Lodge. While the results of the 2016 census have not yet been released, the estimates are that there are now over 1,000 mountain gorillas in the wild, between Bwindi National Park in Uganda, and the Virunga Massif. Stay tuned for up-to date information.

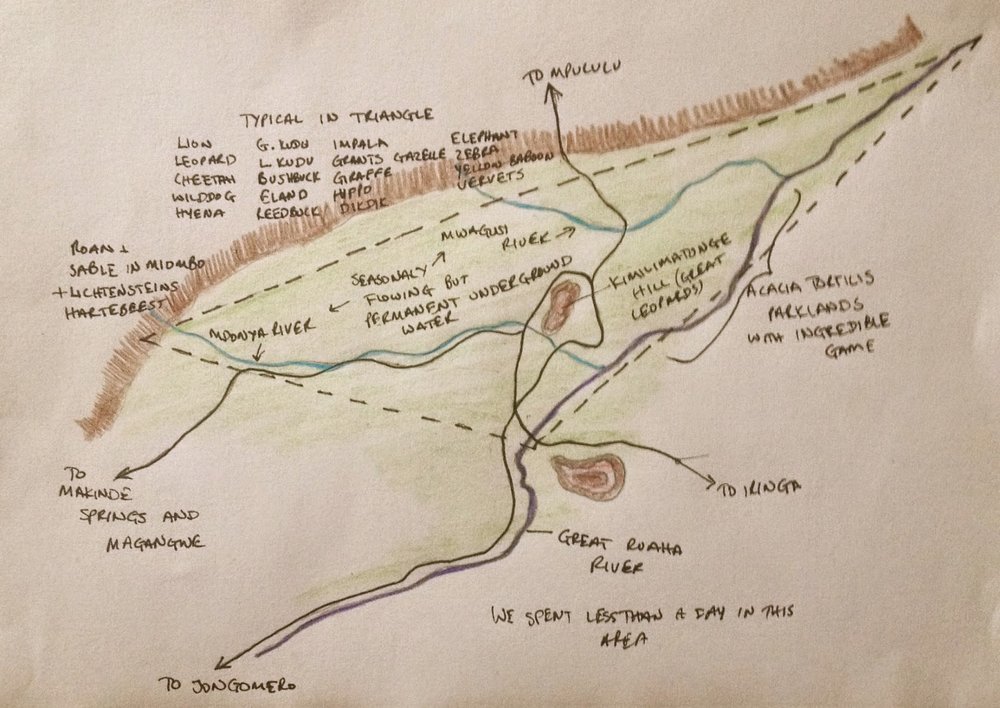

How big is the area that the mountain gorillas live in?

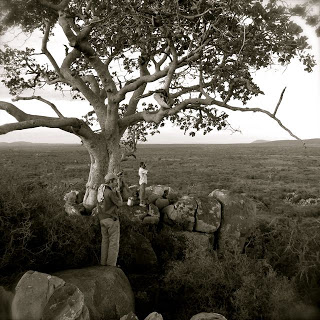

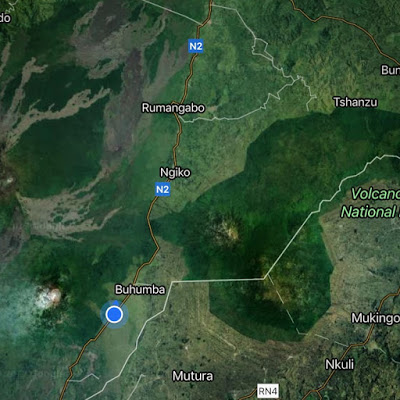

The amount of land that mountain gorillas have in the Virunga massif is on 447km2. You can clearly see the pressure of humans on the land when you look at a satellite image of what is left of the forest. An initiative by the Virunga is buying land adjacent to the park to replant bamboo and expand the area available to the mountain gorillas.

The forest (East) of the N2 in DRC is home of the Mountain gorillas. As you can see, the area of land in DRC is much greater than that in Rwanda.

What do mountain gorillas eat?

Mountain gorillas are vegetarian but occasionally will raid a nest of safari ants (Dorylus sp). and sometimes eat mushrooms. They select from over 60 different species of plants but their favourite is bamboo which may make up to 90% of their diet during bamboo shoot season. The rest of the time, over 75% of their diet consists of 3 species:

(Galium ruwenzoriense, Peucedanum linderi, and Cardus nyassus). A big silverback can eat up to 30kg per day.

The blue sign represents the new park boundary for bamboo project. Expanding the habitat for Mountain Gorillas. The forest in the distance is the current park boundary and limit of Mountain Gorilla habitat.

Are gorillas territorial?

No. Mountain gorilla groups live in overlapping home ranges that vary in size from 3 to 34 km2 depending on group size and food availability. They tend to move less than 1 km per day, resting and feeding for about the same amount of time. Occasionally when they encounter other groups or danger they will travel further, but not usually more than 3 km in a day.

What do you mean by a silverback?

The term silverback refers to a full-grown male gorilla. Male gorillas mature somewhere between 9 and 10 years old. At this time they are already much bigger than the females and the hair on their backs begins to turn white or silver. Somewhere between 12 and 15 years old, they reach their full size and can now begin to compete for females. They are now considered a silverback.

Humba's son poses for the camera.

Who is Humba?

While the specific make up of each gorilla group is different, gorilla groups are led by a dominant silverback. It isn’t completely straight forward and there’s a lot that is going on that we can’t see, but it seems that females choose who to follow. Remember, these are highly intelligent primates. Dominant silverbacks will usually tolerate other silverbacks in their group either because they are their sons, but occasionally they will also tolerate non-related silverbacks in the group- it is after all advantageous to have a strong coalition when they do encounter other gorilla groups to help guard the females from being abducted or convinced to join the other group.

Silverbacks are very protective of their groups and will display and act violently towards perceived threats including lone males and other gorilla groups.

How do you tell the difference between a male and female gorilla?

It is actually quite difficult to tell the difference between a young male and young female gorilla unless you see the penis. Gorillas have internal testicles so you can’t go by that visual cue either. However, adult gorillas exhibit sexual dimorphism (the fancy word for males & females looking different)- mainly in size and the obvious “silver-back” of a fully mature male. An adult male gorilla can weigh more than 155 kg which is almost twice what a big female weighs (80kg). If you could look at their skulls, you’d also see that the males have bigger skulls with a very pronounced sagittal crest. This is the attachment for the chewing muscles. They also have fairly large canines.

What is a gorilla’s life like?

Babies are born after a 255-day gestation period. They weigh about 2kg at birth. Twins are sometimes born, but it is very stressful for the mother and they rarely survive. 18% of infants die in the first six months- and the mortality is higher in the wet season because of respiratory diseases. Another 16% will not make it to 3 years, but after that they have a good chance of surviving to adulthood (8 years).

Females mature at 7-9yrs and usually have their first baby at 10. From then on they have babies about every 4 years for the next 20 years.

When males mature, they will often leave the group they were born into and join small groups of males or become solitary hoping to start their own families. Mature females also leave the groups they were born into and either join other groups or solitary males to form new groups.

What is a typical day on a gorilla trek?

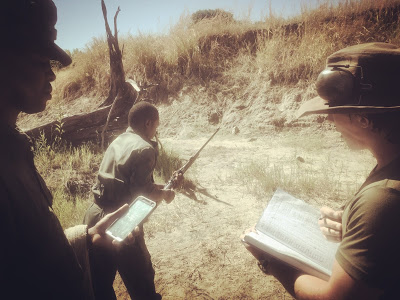

Usually somewhere between 6 a.m. and 7 a.m. small bands of trackers and rangers head out to find the gorilla groups. They do this regardless of whether any tourist is going to visit for monitoring purposes. Because the gorillas tend not to move that far, the trackers head out to where they saw them last and begin tracking from there.

Meanwhile, back at the ranger’s station, you are waiting for the registration process to begin. You’ll have your permit in hand and you fill in your details including passport number into a book and then sit down to wait for a briefing. It is fairly simple in Virunga, because there are fewer groups, and fewer people visiting, so you all sit in one room and the head ranger explains gives a short explanation of the gorilla groups and which ones you will visit. When you are ready to go, the rangers distribute facial masks and ask you to sanitize your hands.

At this point if you would like a porter to help you with your bag (and hold your hand on the slippery slopes) they are waiting outside ($15 fee per porter paid directly to the porter). You can also buy a walking stick for $10.

Once this is done you head off on the walk. The rangers have a fairly good idea of how long it will take to get to each gorilla group so you head off through the fields adjacent to the park to one of the numerous paths that enter the forest. When you enter the beautiful forest you head along a network of paths to where the trackers have found the gorilla group that you will visit. The trek can be anywhere from 20 minutes to 3 hours. You leave your bags and take only your cameras. I recommend carrying an extra camera battery and memory card in your pocket because you will likely take a lot of photos and video. You will don your mask and slowly approach the mountain gorillas. The rangers will vocalize to the gorillas to let them know that everything is ok and you will begin your 1 hour with the gorillas. This is non-negotiable, but if you want to spend more than 1 hour per day with gorillas, and have a relatively good fitness level - contact me. In my experience, the rangers are keen to get you in good photographic opportunities so sticking close to them often gets you in the best places. Your hour will go by fast. Then it is time to head back to the ranger post where your trek ends.

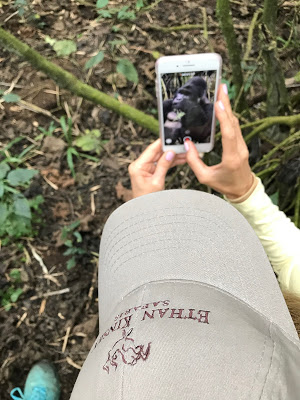

Sometimes all you need is an iphone and a cool hat.

How should I behave in front of the gorillas?

Be silent in the presence of the gorillas.

No smoking

No eating or drinking

Do not stare or point directly at the gorillas

NO FLASH photography

Follow the guide's instructions/actions.

Move slowly and calmly

Should the Silverback charge, do not run.

Keep behind the guides.

No children under 15 in Rwanda, no children under 12 in DRC (non-negotiable)

Wear the surgical mask provided by the rangers in the presence of the gorillas.

Gorillas are highly susceptible to most human diseases and if you are knowingly carrying a contagious disease (especially flu) please DO NOT attempt to trek. This is because they are so closely related to us: read this awesome article about how close we are.

How fit do I need to be and what if I can’t walk?

This is one of those questions where the ideal fitness and minimum fitness are going to differ greatly. Mountain gorillas are found above 1,800m above sea level (5900ft). The forest paths are uneven and can be slippery- and any given group could be from 500m to more than 10km from the ranger post. Of course it is very unlikely that you will find that all the groups are deep in the forest or far away- the shortest walk I ever did in DRC to see Humba was less than 200m, but I’ve also walked for 3hrs with fit people to get to a group. The rangers will take your fitness or ability to walk into consideration but you should be able to walk a couple miles and be able to deal with some hills. If you are unfit, definitely hire a porter to hold your hand. Remember, a lot of it is in your mind. If for one reason or another you cannot walk, but would like to see the gorillas, it is a great opportunity to inject some cash into the local economy. Many of the villages in DRC are inaccessibly by car so the people have large woven baskets called Kipois that they use to carry people who can’t walk (or royalty) to roads. It costs $250 to be carried to a gorilla group.

What should I wear for the gorilla trek?

The key things to think about when packing for Rwanda or Congo are as follows:

There is a high potential that you will encounter wet weather,

The trekking can be slippery and steep and you may need to scramble over fallen log.

There are stinging nettles in the forest that can be quite uncomfortable when brushed against, and there are safari ants known locally as Siafu that can also be unpleasant.

The essentials to wear:

Strong waterproof walking boots

Wicking sock liners and hiking socks- it is really useful if you can pull your socks up over your long trousers to prevent ants from crawling up your pants. Gators can be very useful as an option.

Long sleeved shirt (or risk nettles)

Long trousers/pants helps with nettles.

I often just wear my rain-pants over shorts.

Sunscreen SPF 30 or more

If you need glasses or wear contacts carry an extra pair of glasses

Things to have in your day pack:

Warm fleece

Rain jacket/ ponch

2 spare batteries & 2 extra memory cards

drinking water

high-energy/protein snack

personal pertinent medication

valuables like passport and money

Additional optionals:

Insect repellent (Avon Skin So Soft is an effective insect repellent) but there are few biting insects that you will encounter in the forest.

Binoculars (not necessary with the gorillas) but if you like birding there are some spectacular birds

Garden gloves

What camera lenses should I take?

This is always a little bit of a tricky question to answer because it depends on the type of photo you are looking for. I only use my iPhone which also takes good video but is quite limiting- I can’t get the close up of the eyes etc. If you are a wildlife photographer and you have two camera bodies you’ll want a 24-70mm and a 100-400mm lens. If you can only have one of the above- the 100-400mm lens will be most versatile. The ability to open up the aperture and lets as much light in will also be very useful in the forest which can be quite dark. There is always a chance of rain when you’re with the gorillas so make sure you have a way to keep your cameras and equipment dry. There are some awkward but nifty rain-jackets for cameras that allow you to continue taking photos when it is raining.

You’ll be surprised how many photos you take so make sure you have plenty of memory, spare batteries and a way to back your photos up.

The other thing to consider if you are a serious photographer is that during the one hour you spend with the gorillas, you’ll only have a fraction of the time when the conditions are right for the photo you’re looking for- whether it is light, gorillas posing, or whatever you are trying to capture. This makes it essential to do more than one trek. Furthermore, you’ll often spend the first 30-45 minutes just getting used to the shooting conditions.

What are the difference between visiting the gorillas in Rwanda & DRC?

There is no difference in gorilla behaviour between Rwanda and DRC except for the natural difference between individuals and groups.

The maximum number of people per trek in Rwanda: 8

The maximum number of people per trek in DRC: depends on the gorilla group size- 4 if the group has less than 10 individuals, 6 if the group has more than 10.

Minimum age in Rwanda: 15 yrs

Minimum age in DRC: 12 yrs

Cost of gorilla permit in Rwanda: $1,500

Cost of gorilla permit in DRC: $400 high season, $200 low season (contact me for low season dates).

Obligatory to wear a surgical mask in DRC for the protection of the gorillas.

More accommodation options in Rwanda

Rangers speak better English in Rwanda

Registration process in Rwanda is done by your driver/guide

Registration process in DRC is done by yourself

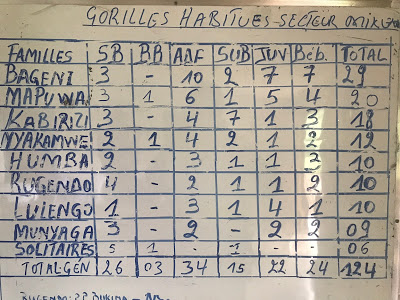

Habituated gorilla groups in Rwanda: 10

Habituated gorilla groups in DRC: 8 but only 6 accessible from Bukima