Our private camp in Tarangire.

The sun was setting: a typical Tarangire sunset that turns the sky an amazing orange, framing cliché Umbrella acacias and baobab trees. The campfire was lit and the solar-heated water showers were being hoisted into the tree. One of the kids was climbing a fallen tree and setting up the go-pro for a time-lapse photo. It had been a long and good day. After a game drive lasting nearly 10 hours, we’d seen so much: herds of elephants coming to the swamp to drink, countless zebra sightings, impala, giraffe, a leopard in a tree, and a lion by a termite mound, not to mention additions to the bird-list that the oldest boy was keeping. We’d even seen a snake: a Rufous-beaked snake, (not an everyday sighting).

A pride of lions had begun roaring a few hundred meters upwind at 5:30 in the morning, close enough that even a seasoned safari go-er would say it was close. A troop of baboons was trying to get to the tall sycamore fig-tree that was in camp, but had to settle for the sausage trees on the edge of camp. It was the epitome of the immersion experience.

The next morning, we woke at again at dawn. The wildlife hadn’t been quieter, but everyone had slept soundly. The kettle of cowboy coffee simmered on the campfire as we discussed the day’s plans. It was going to be another long day of driving, but with the opportunity to see rural life in Tanzania. Our destination was also exciting as we were preparing to spend a couple nights camped in a remote part of the Eyasi basin among the Hadzabe.

The last part of the drive is an adventure in itself. Low-range is engaged and the car crawls up the hill, rock by rock until finally the track levels out and, sheltered by a rock, camp is found, exactly the same camp as in Tarangire. It wasn’t long before we were sitting on top of the rock, overlooking historic Hadza hunting and gathering grounds, watching the sun go down once again.

A Hadza high up in a baobab after following a honeyguide to the beehive.

The next morning, a small group of Hadza hunters walked into camp. One had already shot a hyrax and had it tucked in his belt. Honey axes slung over their shoulders and bow and arrows in hand, they lead us to where some women had begun digging for tubers. We were soon all distracted by the excitement of finding kanoa, or stingless-bee honey. Another distraction ensued when a Greater honey-guide flew around us, chattering its call to follow. You can’t plan these spontaneous, magical experiences.

Digging for tubers.

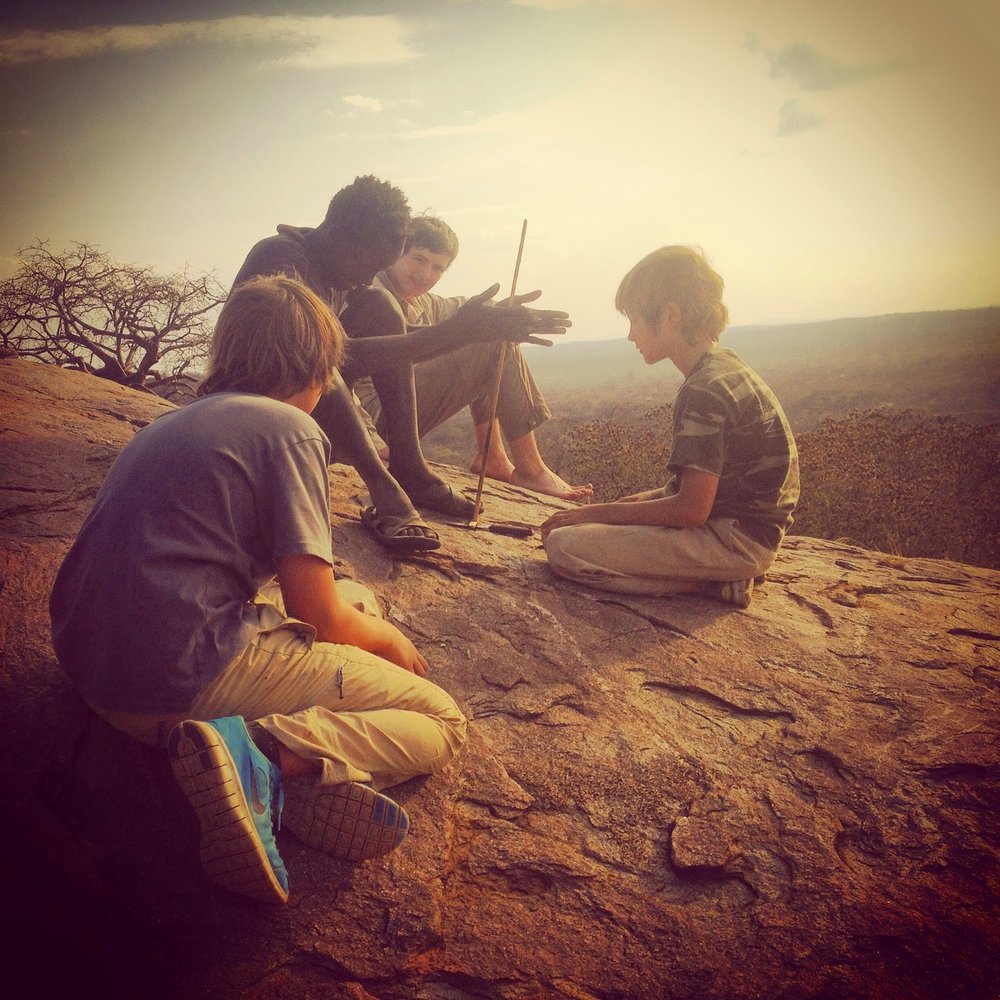

I continued to dig for roots with the women as the family I was guding followed the Hadza guides who in turn followed the bird, eventually finding a tall baobab tree, the hive high-up on the lower side of a massive branch. I don’t know if it is just for fun, but on numerous occasions I’ve watched Hadza climb the baobab trees without smoke to placate the bees and haul out the combs dripping with honey. Judging by the laughter, it seems that they find being stung somewhat comedic. So much for African killer bees. Following a mid-morning snack of honey, bees wax, roasted roots and hyrax liver (no kidding, everyone tried!) we returned to camp for a more traditional (for us) sandwich after which the Hadza hunters showed the boys how to make arrows and fire, and in the evening took them on a short hunt.

Making fire!

Now your turn!

The last attempt for a hyrax before heading back to camp.

Having spent the first four nights of the trip in the light-weight mobile camp, we next made our way to more luxurious accommodations, swimming pools, lawns to play soccer on, and unlimited hot showers.

A budding wildlife film-maker watches as a breeding herd of elephants cross the plains in front of us. (Northern Serengeti)

There is something about privacy and after visiting Ngorongoro Crater, we were all happy to be headed to the more classic luxury mobile camp in Serengeti; not for the luxury, but for the privacy. We’d timed it perfectly, and rains in the northwest of Serengeti were drawing wildebeest herds back toward the Nyamalumbwa hills, also a sanctuary for black rhino.

Watching giraffes or are they watching us?