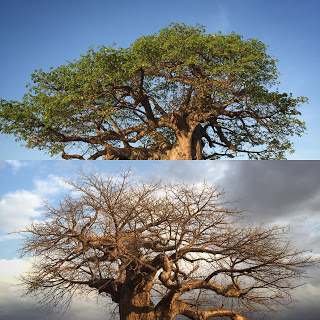

Same baobab tree, 11 days apart, slightly different angle.

Ruaha is just that far away that it doesn’t make it into enough of my safari itineraries. This year I was fortunate to have two back to back safaris in Ruaha, giving me two weeks in the park at one of the best times to be there.

I’ve written about Ruaha in other articles about walking safaris or exploring the more remote areas of the park. However over these two weeks, most of the time I spent was in the core area- a triangle between the escarpment, Mdonya River, and Great Ruaha River. Being the end of the dry season, water had ceased to flow in the Ruaha and elephants, warthogs, zebra and baboon dug in the sand rivers to get at the cool water that flowed beneath the sand. The predators staked these points out, waiting in ambush, for whatever prey overcome by thirst would venture too close without a careful scan.

Within a few days of me being there, the rains came. Big, violent thunderstorms that brought with them relief. Change was overnight. Areas that had been doused with water began the transformation into an emerald paradise. Fragile buds pushed through the soils crust, the tips of dead-grey branches began to bud, while other plants threw sprays of fragrant blossoms that filled the air with the scent of jasmine.

The following images and videos were all taken with my phone (for more and better quality follow me on instagram @tembomdogo

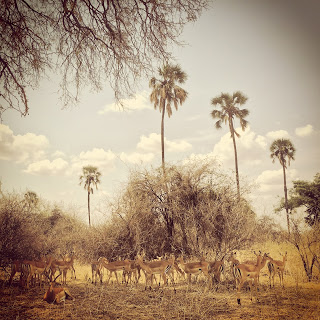

A herd of impala resting in the shade.

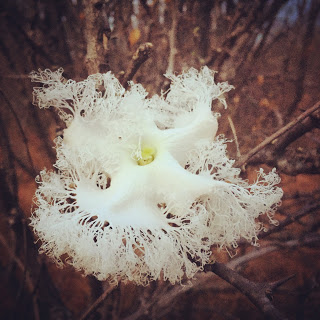

Combretum longispicatum blossom.

A delicate Ribbon-wing lacewing is our dinner guest.

Magic.

Scadoxus multiflorum is a great Latin name for this Fireball lilly.

The incredible light- what you can't see is the fragrance of jasmine that was drifting in the air from the blossoms of this bush.

Fresh growth on Combretum apiculatum.

Sesamothamnus blossom- another fragrant beauty.

Lillies on a walk.

Never smile at a crocodile- unless you're a Ruaha lion that specializes in hunting crocodiles.