If we needed a species as an icon to represent the conservation of Virunga National Park, in the DRC, it would be the Mountain Gorilla, or Gorilla beringei beringei, as it is known to taxonomists. In fact, it could be argued that without Mountain gorillas, the National Park, established in 1925 and formerly known as Albert National Park, wouldn’t exist today. Paradoxically, it was two collectors of gorillas for museums that recognized the unsustainable collection of Mountain gorillas. Charles Akeley who collected for the New York Museum of Natural History, and Prince William of Sweden with their prominent connections were able to lobby the Belgian King and gather international support to establish the protection of Mountain gorillas.

The gorilla story in DRC takes us back to 2 legendary silverbacks, Zunguruka and Rugendo who each led a habituated group of gorillas on different ridges in the forest behind Bukima ranger post. Both were habituated in 1986.

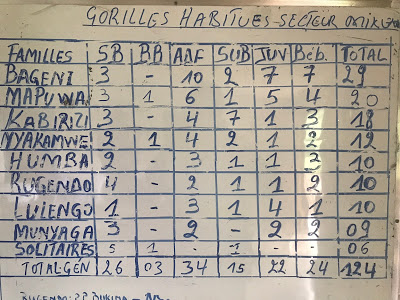

A white board in the rangers office at Bukima showing the group make up. Key: SB: Silverback, BB: Blackback, ADF: Adult Female, SUB: Sub-adult, Juv: Juvenile, Beb: Baby.

Current lead Silverbacks in the six groups accessible from Bukima Ranger Post:

Kabirizi group: Kabirizi

Bageni group: Bageni (Kabirizi's son)

Nyakamwe group: Nyakamwe (Humba's brother, son of Rugendo)

Humba group: Humba (Son of Rugendo)

Rugendo group: Bukima

Munyaga group: Mawazo (& Kasole)

Two stories:

Rugendo

Zunguruka

If all of Rugendo’s sons are his, he could potentially be one of the most successful silverbacks to have led a gorilla group. At the time that he led it, it was a large group of 18 individuals. His son's names are highlighted in bold-italic.

Rugendo was tragically assassinated on the 15th July, 2001, in crossfire between warring militias, however, his genetics and legacy live on.

Rugendo had many sons:

Mapuwa

Left his father’s group in 1998, with two females.

Humba

Nyakamwe

Humba left with his brother Nyakamwe in 1998. In 2014 they interacted and split into two groups.

Senkwekwe

Senkwekwe took over the group, though as a young silverback he lacked the strength and experience to keep the group intact. Some of the females left, joining his brother’s group Mapuwa. Senkweke was murdered together with five other gorillas in 2007.

Bukima

(not Rugendo’s son) Is currently the dominant silverback of the Rugendo group. Kongoman and Baseka are both with him.

Kongoman

Baseka

Ruzirabwob a is a solitary silverback.

Zunguruka got his name from the habit of walking in circles. He had two sons, Ndungutse and Salamawho took over the family when Zunguruka died of old age.

In 1994, a wild silverback showed up on the scene and fought with Salama and Ndungutse. He did not win, but the wounds he inflicted on Salama eventually killed him leaving Ndungutse as the sole silverback.

The wild silverback was named Kabirizi.

In 1997, Ndungutse was assassinated. His sons Buhaya and Karateka took over the group, and after a series of fights, Karateka ended up as a solitary silverback.

At this point, Kabirizi returned to the scene and killed Buhaya. The females however refused to follow Kabirizi and were led by the oldest female Nsekuye.

At this point Munyaga, a lone silverback entered the scene and took over the group being led by Nsekuye. It wasn’t long before Kabirizi challenged Munyaga, this time winning and taking with him all the females. Munyaga remained with a small group of sub-adult males. Then in 2007 he went missing during a surge in rebel activities. At that time, Mawazo led the group although he was still a Blackback. He eventually matured and was able to acquire females of his own with his brother Kasole.

Kabirizi continued to succesfully lead his group that grew to 36 individuals. Then in 2013 he suffered a blow when his son Bageni, who had grown up to become a formidable Silverback, challenged him taking with him 20 individuals, including his mother, brother, and 2 sisters.