As water sources dry up in southern Serengeti, more than 1.5 million wildebeest begin to make their way north toward the permanent river called the Mara. While the exact arrival is dictated by the extent of the drying and rainfall in northern Serengeti and Kenya’s Maasai Mara, they usually arrive in mid-July. Again, depending on where the greener pastures are, they move back and forth across the Mara river, in and out of Kenya, following the sporadic thunderstorms.

Us watching as thousands of wildebeest plunge into the river below us. Photo credit: Pietro Luraschi.

We arrived at Singita Mara Camp, by far the most luxurious camp in northern Serengeti, on the 3rd of August. The herds had already crossed the river heading north, and some were making their way back across. Just the sheer numbers of wildebeest was incredible as we slowly drove the northern bank of the river looking for an aggregation that looked to cross imminently. Patience, patience… but we didn’t need much as we found a group many thousand strong gathering on the banks of the river. The milling back and forth, the reluctance of the wildebeest- whether it is fear of the cold rushing water, or fear of the crocodiles submerged with only their eyes and nostrils above water, I do not know, but it adds to the excitement (and sometimes frustration).

Here is an amusing cartoon about it. When they do start to cross, it just goes and goes and goes until there are no more wildebeest left. The energy is incredible. Then it stops and the milling resumes, this time, mothers looking for their babies and babies looking for their mothers.

(The video below shows what we were seeing)

This could be your private lunch banquet in the Serengeti plains.

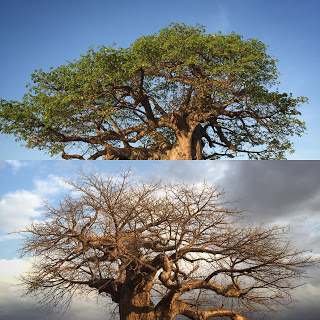

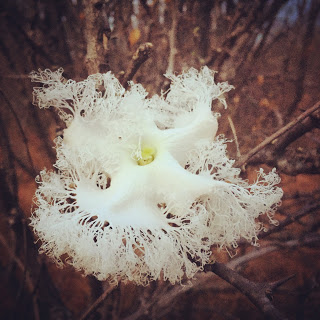

Of course, there is more to the Serengeti (and northern Tanzania) than the migration so we also included a couple days in Tarangire National Park, where there is a daily migration of elephants to the permanent water sources. The landscape is also different with the typical red African soils and eccentric Baobab trees that dot the ridges, offering a nice contrast to Serengeti’s woodlands and plains.

This is a classic Tarangire scene. Elephants walking into the sunset with a magestic baobab tree in the foreground.