An exploratory guide's-only trip.

Greater kudu- a flagship Ruaha species.

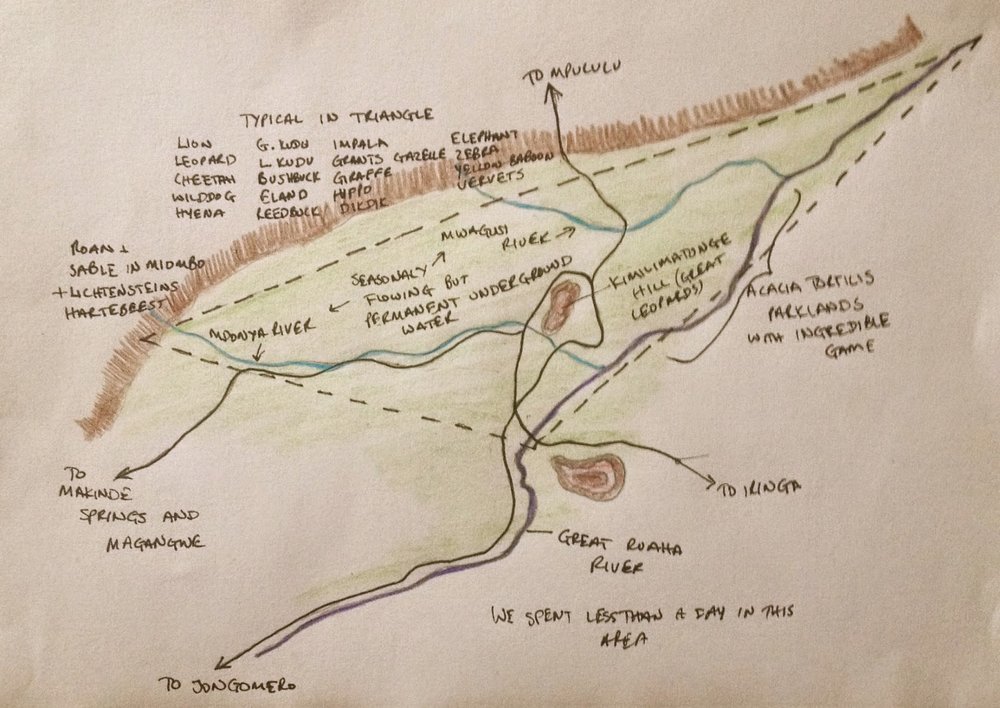

There’s a triangle in Ruaha National Park, bordered on the south side by the Mdonya river, the escarpment running north east, and on the east to south side by a section of the Ruaha River’s floodplain. Through the middle runs a sand river, the Mwagusi, creating an incredible area for the charismatic wildlife that gives East Africa its reputation. Like many places in East Africa, water is the limiting resource that determines wildlife abundance, and the Ruaha, Mwagusi and Mdonya Rivers provide just that- permanent (though not always obvious) water for herds of hundreds of buffalo, elephants, giraffe, zebra, impala, yellow baboons, and their predators: lions, leopards and cheetah. But it is a relatively small area in Ruaha’s extensive landscape.

Our first stop was a campsite on the Mdonya River. It was the end of the dry season, so water was limited to a few places where elephants knew to dig. We’d just driven 15 hours straight from Arusha, but were sighing in relief as the familiar sounds of the African bush comforted our souls. None of us bothered with the rain flies for our tents and went to sleep to the sound of the African scops owl. Lions roared as the walked by at about 4 a.m. but it wasn’t until the ring-necked doves started their morning call to work that Tom, our camp assistant, woke up to stoke the fire and get the coffee going.

Our first campsite under a Lebombo wattle (Newtonia hildebrantii).

Day 1.

Our first order of the day was a meeting with the tourism warden and a couple of rangers to discuss our expedition. Some recently opened roads were making access into some of the least visited areas of the park possible and we wanted to know if they would work for walking safaris. For many of us, walking is a way of experiencing a quieter side of nature and escaping from the diesel-engine-run game drives and trappings of luxury camping. Waking up to a thermos of coffee and going to bed after a sipping whiskey by the fire were all the luxury we needed; it was about the wilderness.

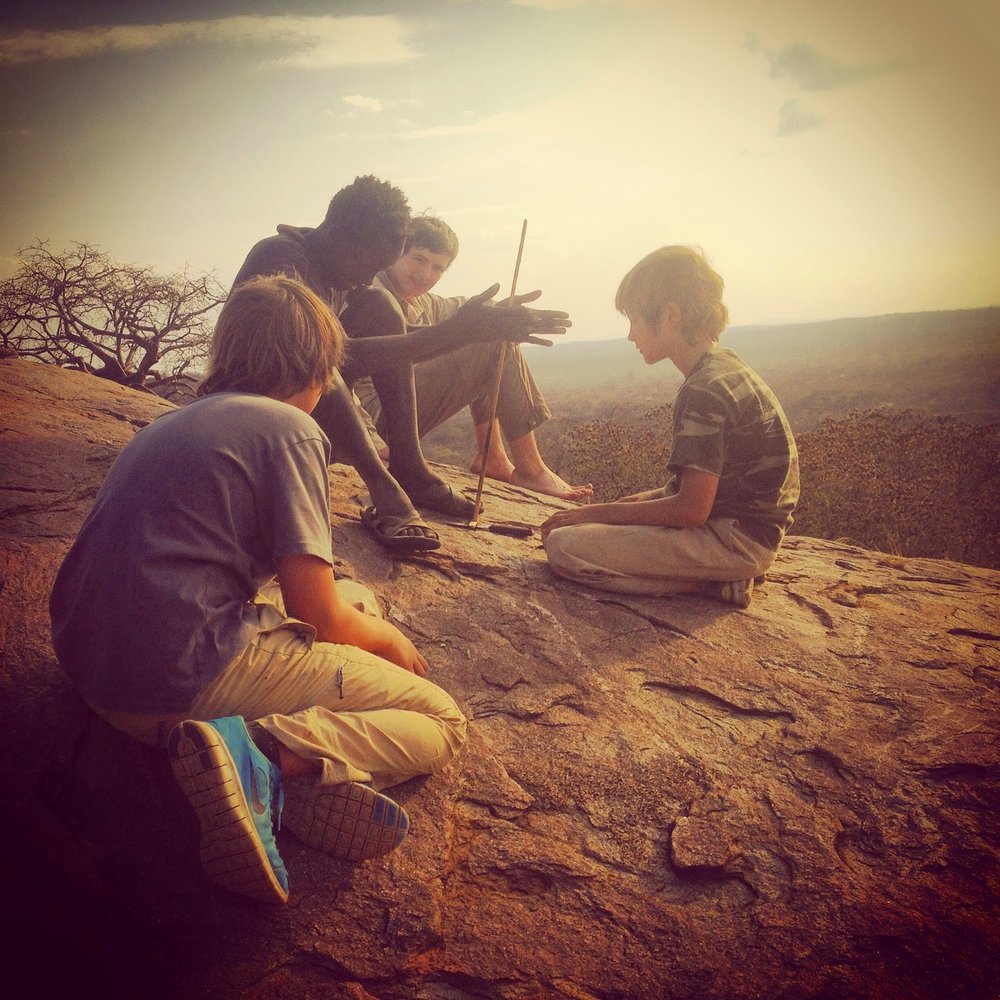

The magical triangle in Ruaha- see map below for context.

As we left the magic triangle we climbed up into the hills behind the escarpment and were rewarded immediately by a racquet-tailed roller who fluttered along side. “Lifers” were being added to the list and for most guides with passion like us, that is one of the most exciting things. The next lifer for a few of us, only a few minutes later, was a herd of Sable antelope: one of the most beautiful of all antelopes, and particularly exciting as they are miombo woodland specialists. The miombo woodland was also changing in anticipation of the rains, and with colors that would compete with a Vermont autumn. Vivid reds, purples, blue-greens, light greens; it was beautiful.

With 7 of us in the vehicle, food for 8 days, camping equipment, and our libraries, water was our biggest challenge. The 90 litres we could carry required us to take every opportunity we could to refill, and determined our campsites over the next few days.

We arrived at the first campsite as the evening light became intense and vibrant and what unfolded became the schedule for the next week: unload, set up tents, collect firewood and light fire, unpack and prep dinner, carry the basin to the stream to bathe and then sip on a cold beer, reclining on thermarests, binoculars on chests, and reference books open. We didn’t need to meditate or even think about focusing on the moment; it just was, pure, the product of a love of wilderness and like-mindedness. Sleep came quickly, as it does in the bush.

Racket-tailed rollers.

Day 2

As the night sky began to change, the fire was stoked and coffee water boiled. Each of us woke to our own beat, grabbed a cup of coffee and the first moments of the day were appreciated in respectful quiet.

With heavy rainstorms imminent we followed Thad’s suggestion and headed to the furthest point we wanted to reach. The grass got greener and longer as we drove around the Kimbi Mountains. We saw more game that day: sable, zebra, giraffe, warthog, Lichtenstein’s hartebeest and even some lions. However, to say that wildlife was prolific would be very misleading.

Lichtenstein's hartebeest- a miombo speciality.

On maps, the Mzombe-roundabout appears to be the headwaters of the river. It is also on the border of the park; in essence, the end of the road. The grader driver literally created a cul-de-sac roundabout. In the past, the Petersons had walked the Mzombe River further downstream before trophy hunting and administration in the bordering Rungwe Game Reserve had become so profit-oriented that they stopped respecting the buffer to the park and hunted right to the edge. Yet, the Petersons’ stories of encounters with lions, elephants, hippos and more had left an impression of this river, one that was not fulfilled at the headwaters.

Incredible flowers.

A natural bouquet. Nature does it better.

Delicate Orchids- Eulophia coculata.

Instead it was incredibly green, and the hills invited walking. It had obviously rained enough to bring out the wildflowers and on the walk the next day in addition to wonderful birds like thick-billed cuckoos, spotted creepers, and yellow-bellied hyliotas, we admired the proliferation of flowers.

Day 3

Having walked for 7 hours in the morning, we returned to camp for lunch. The clouds were building and we had already been dumped on while walking. We packed up camp, and made our way back around the mountain. Our third camp was at the base of the mountains in a small clearing. Purple crested turaccos hopped around in the trees and as darkness fell, barred-owlets, tiny little owls, began calling.

Water re-filling break under a Faidherbia albida.

Day 4

The next morning we set off early, and were fortunate to quickly find a proper elephant trail leading up into the hills. Elephants are big animals and just naturally take the best route. The switchbacks were there when we needed them and the path that wound its way up around rocks and to the top of the hills made it a real pleasure to climb the hill. A rocky outcrop distracted us as we paused for peanuts, homemade cookies and water. More new birds made our list but a particular highlight was 2 sightings of Chequered elephant-shrew.

Photographs cannot capture the extensiveness of this wilderness.

We returned to camp at around 3, exhilarated by the climb. Lunch was quick and we headed off to a clearing we had passed a couple of days before that we believed we could drive down to get to a river known as the Lupati, a tributary of the Mzombe. We barely made it half a kilometre when the woodland became too thick to drive through. Small drainages were converging and a couple of times we ran into dead-ends. We did have good sightings of Roan antelope and that evening as we watched nightjars hawk the sky, we heard our first elephants.

Just a lunchtime chill.

Day 5

Spectacular storm build-ups warned us that we should probably head back to the Ruaha River, so after our usual breakfast we took a shorter walk before proceeding to head towards Usangu. We entered the new addition to the national park and drove and drove. It was a long day of driving, but the landscape kept changing as we pushed on. It was not until we made it into the lower areas that we began to see more wildlife, particularly giraffe and impala. There was evidence of game and in one clearing we had great sighting of sable, roan, and bush pigs foraging in daylight. Scuff marks and tracks in the road told a story of Africa wilddogs killing a warthog.

Roan antelope- another Ruaha speciality.

We arrived in camp as it was getting dark. Camp was on the river, just meters from a pool with over thirty hippos in it. We quickly set up camp before settling down on the riverbank to watch the birds fly by and hippos grunt their disapproval of their new neighbors. As darkness set in, we scanned the water for crocodile eyes- 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 pairs of eyes watching us.

Day 6

The sun had not come up yet, but the sky was changing. Coffee cups in one hand, binoculars ready to train on birds flying by, we sat and watched. This was really a grand finale for us. It was a slightly slow start but this was the area we would most likely come to walk next year and I wanted to explore. We set off for a couple of hours and then returned to take the vehicle. There were campsites we needed to examine and stretches of river to see. The roads had not been graded as they had the previous days, and the going was tough enough that my vehicle is being repainted as we speak. A stump wrote off a tire, but those are the costs of adventure.

Pel's fishing owl.

Day 7

It was the usual morning routine, but as we sipped our coffee and contemplated the view, we knew we were leaving today. We took down our tents and then took a quick walk along the river before climbing back into the vehicle for the ride home.