In my attempt to share experiences I find myself often writing trip reports that read a bit like a fill in the blank story. “I went to …., and I saw … Then I went to… and I saw …”. The wildlife viewing on the last back-to-back safaris was phenomenal. The list itself is impressive, but the experiences themselves were unbelievable. It seemed that every day topped the previous, and we couldn’t imagine how it could go on… but it did. I don’t want to get into the list, but I’ll write about a few select highlights.

Happy New Year- Day 2. Rubondo Island. Cats. Late for Lunch. An Unusual Hyena.

A Happy New Year!

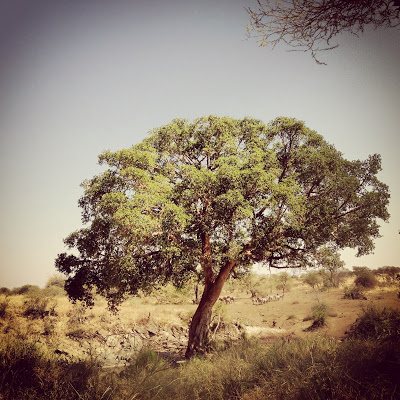

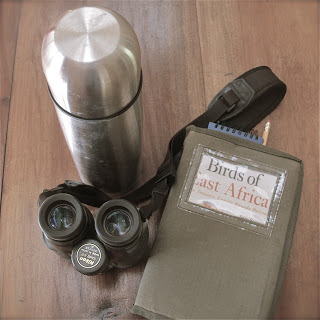

As I opened the game viewing roof of my car at 5:30 a.m., a chilly wind sent shivers down my spine. Had I really convinced my guests to get up before sunrise on New Year’s Day? The sighting of 13 African wilddogs on a kill by other guests the evening before was enough to persuade me to enthuse my guests to get up for an animal they’d never heard of. After a quick cup of coffee, and with dawn quickly threatening over the horizon, we crept out of camp. A Kori bustard displaying the white of his under tail stood out in the darkness as I wove my car across the wildebeest migration trails along the edge of a large depression. Lappet-faced vultures roosting on Acacia trees stood out against the changing sky.

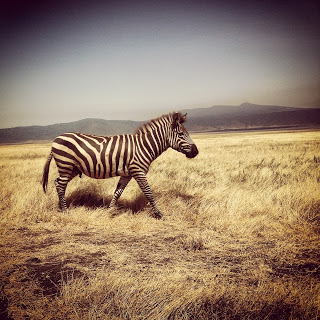

I stopped every few hundred meters and stood on my seat, elbows rested on the roof of the car, binoculars pressed against my face looking for a sign; the typical formation of wilddogs heading off on a hunt, the flash of white tail tips, panicking gazelle or wildebeest… something. A zebra brayed, and my binoculars scanned in his direction and caught a familiar trot that indicates danger. It was still a little too dark so I had to stare longer than usual to allow the opportunity for my eyes to adjust. But there they were. It is truly a beautiful moment and a nostalgic one for me which brings back memories of chasing wilddogs in Piyaya. What a thrill… my first wildlife sighting of the New Year was a pack of wilddogs.

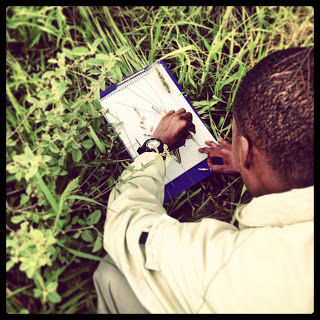

Few first time visitors to Africa understand the magic of wilddogs. Once common in the Serengeti, their population has struggled throughout Africa as a result of persecution from pastoralists and contact with domestic carnivore diseases. As co-operative breeders, only the alpha male and female breed The need at least 4, if not more, helpers to help raise their pups. Sharing their food through regurgitation and the constant reinforcement of the hierarchy through facial licking has made them vulnerable to diseases that can easily wipe out the whole pack.

The obligation to regurgitate, especially to feed puppies and dogs higher in the hierarchy means that the members of the pack generally get hungry at the same time. It’s predictable, and there’s usually a leader who sets off quickly followed by the rest of the pack. There’s no patient stalking and waiting like the cats, or strategic flanking like the lions. Instead it’s a bold trot in a loose arrow-head formation with no attempt to hide. It must be one of the most terrifying moments for a gazelle, impala, or wildebeest. The pace increases with sightings of prey and, once an individual is selected, can reach 60km/h, kilometer after kilometer. Prey has little chance, but it is exhilarating to follow.

We sat with the dogs for nearly two hours, watching them play, their curious nature bringing the younger pups closer to the vehicle. The alpha male guarded the female and I suspect that within the next couple months they will be whelping and the pack will grow by 8-12 puppies.