Day 1

With renewed enthusiasm for a place that keeps ending up as my private playground, Saturday saw me back in Olduvai Gorge having a picnic on the 2-million year old lava and tuff. Having just spent a fascinating hour in the Oldupai museum, looking at the collection and reconstructions of skulls, bones and stone tools displayed at the museum, I cut brown bread with a stainless steel knife on a ceramic plate, poured cold white wine into wine glasses, and contemplated the advancement of tools and objects that may be unearthed millions of years from now. My mind was on evolution, changing landscapes, evidence, and the gaps of knowledge of the Earth’s History. I’d never noticed the photos of the Leakeys with dinosaur bones in southern Tanzania, but after an interesting conversation and a hyper link to a National Geographic Article, it had me wondering what was buried under the rock I was standing on between the deepest underlying rock (570 million years) of the Gol mountains and the 2 million year old basalt. How much do we really know?

http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2010/03/100303-dinosaurs-older-than-thought-10-million/

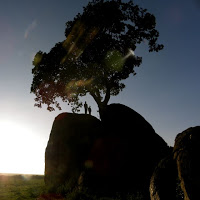

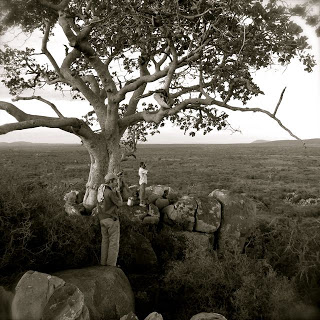

Our journey continued, the same track I’d taken last week, but as always- never the same. The wildebeest migration is driven by their need for water and already, there were signs that they were preparing to moving back towards the permanent water sources in southern Serengeti. There was still enough grass on the plains that the wildebeest couldn’t resist, but their thirst kept driving them into never-ending lines as they made their daily trek to the last remaining water. We stopped in front of Nasera rock to watch a dung beetle rolling his prize to the random spot he’d bury it… slowly adding fertilized layers to the soils that covered the most recent tuff- of the last 30,000 years. The big picture can quickly overwhelm me- the uncomprehendable millions of years and the hundreds of thousands of years, to the near insignificant tens of thousands of years and all the interdependences, delicate balances, and implications that we’ve only really uncovered and documented in the last few hundred years let alone decades.

Take these figures for example- dung beetles roll away 75% of the dung produced in the Serengeti. The soil itself is 15-20% made up of dung beetle balls. Without dung-beetles the Serengeti wouldn’t support the nearly 3 million mammals.

Day 2 & 3

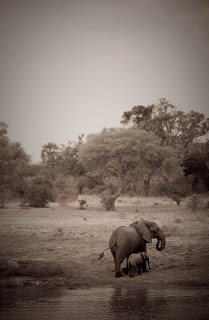

Hot coffee served from stainless steel French-presses set the morning off as we trolled out onto the plains. The wildebeest gathering as they headed towards the remaining water on the plains amused and awed us with their repetitive gnuing, their blank-stare faces, and the infinite numbers gathering on the plain.

This amateur video clip shows images of our morning game drive.

(apologies, due to slow internet I am having trouble uploading videos to this page)

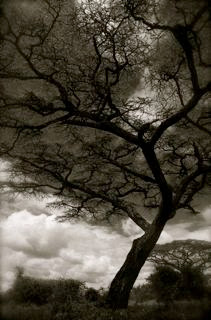

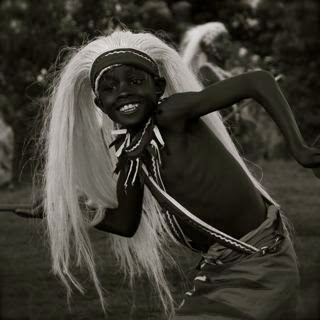

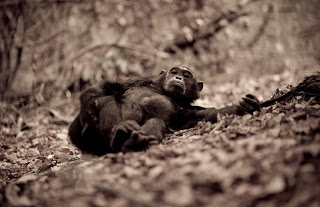

I’ve posted images with captions of the rest of the trip and a video clip of lions feasting on day 3. The only thing I didn’t get a photo of was the aardvark that was digging in the road or the 11 lions we saw on the night drive. This time I don’t have words and I’ll let the images speak.

Day 4

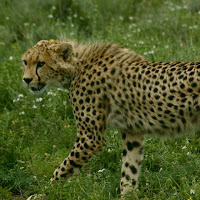

These mother cheetah and her cub entertained us with a failed hunt before we said goodbye to the Serengeti plains and headed up through Ngorongoro back home.