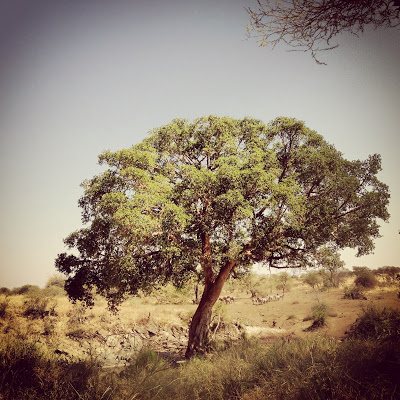

My office under a baobab tree.

The lilies bloom.

A few weeks ago, I found myself sitting in the back of my open vehicle under a massive baobab tree, staring across the vast expanse of a tiny portion of Ruaha National Park. A lone antenna on a far away hill beamed an unreliable cell-phone signal that allowed me to send various emails and of course the occasional instagram photo (and to call my lovely wife). Around me the grass was green and the sky a Polaroid blue interrupted only by a few cumulus clouds. Woodland kingfishers reestablished their territories, and flocks of Eurasian bee-eaters and rollers patrolled the skies feasting on the termite irruptions, joined by other migrants such as Amur falcons and kestrels.

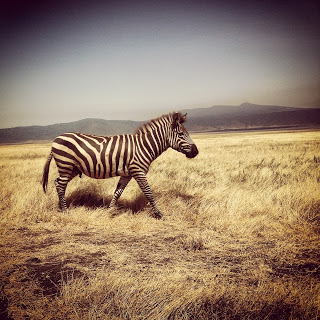

Seven weeks prior, I arrived in Ruaha to begin the second round of training rangers. The Pilatus flew over the Ruaha River, or what used to be the Great Ruaha River. Unregulated rice farming upstream and an illegally overgrazed, but now recovering, Usangu swamp have reduced the river to a few pools of hippo dung-infested water. The animal trails were clear when we flew over and spread like nerve ganglia from any form of drinking water. Ash lay in white shapes against the red earth, evidence of trees that had burned in grass fires, reminiscent of the chalk drawings used to outline bodies at crime scenes.

The temperature must have been close to 40 degrees Celsius, and the sun unbearable. Even with the windshield down as we drove to camp, the hot blasts of air did little to cool the body. It was pretty clear that the next few weeks were going to be intense. The harsh light and dust in the air immediately forced a squint that would become so permanent for the next weeks that I developed squint-tan lines across my forehead.

A wild ginger.

Like a fresh breath of air.

Building storms accentuated the heat, hinting at relief, but it wasn’t until well into the course that it finally did rain. The seasons do not change in East Africa as they do in the temperate climates. Instead of gradual changes, season changes here are striking distinct events, the zenith of a build up. There’s not half-rain between dry season and wet season, or a half dry between dry and wet season. It is a sudden thunderstorm that leaves you soaked and shivering when only half an hour ago you couldn’t drink enough to keep up with your perspiration.

That first rain is one of the most beautiful moments you can have in the bush. The bush becomes silent, and then the violent raindrops fall, bouncing off the hardened ground. If you go out you’ll notice that none of the animals take cover. Instead they expose themselves, the water washing off months of accumulated dust. Within a couple of days, buds appear on the trees, and little cracks appear in the ground as grass sprouts push through the earth. The next morning, the dry season silence is broken before dawn by migrant birds arriving, and a great weight is lifted while the impala fawns dance. Baby elephants run around trumpeting, no longer stumbling behind their mothers.

Within a week, lilies are flowering and the baobabs go from bare grey branches to dark green leaf. It is an amazing time for training as new life is visible and obvious. Insects that could not survive the dry season irrupt in unbelievable numbers, if only for their ecological role as food for the birds that begin their breeding. Other animals that may not be considered so pleasant also appear. Centipedes, scorpions, and massive spiders patrol the nights- but it’s all part of a big web of interconnectivity that keeps the wilderness wild and healthy. The contrast of obligate, fragile and intricate connections is easier appreciated on foot. The sense of immersion and vulnerability is far more appealing than watching lions sleeping under a tree from the safety of a 4x4. These are among the things that the training course was attempting to teach.

A young leopard tortoise emerges from aestivation after the first rains.

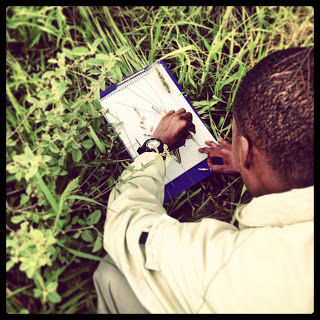

The training we conducted this year built on the training conducted in January: 20 participants, five days Advanced Wilderness First Aid, 10 days firearms training, and two weeks of walking emphasizing safety including dealing with potentially dangerous game. This November we added two weeks of identification, interpretation and further firearms training.

Marksmanship and weapons handling on the firing range with Mark Radloff.

Dr. Amol gives expert instruction in Swahili & English.

Andrew Molinaro goes through the drills- "what happens when an animal does charge"?

Simon Peterson on shot placement- "as a last resort, where are you going to shoot to stop a charging hippo"?

Kigelia africana, a common talking point.

It is a misconception that participating in a guiding course will equip you with in-depth knowledge. Even individuals with advanced academic degrees struggle in identification unless they have extensive field experience. However, the foundations can be laid, seeds of curiosity planted, and skills established enabling and encouraging a student in the right direction. It would be extremely arrogant for us “experts” to not admit that we are learning every day.